Showing food fact sheet for milk

Mooraculous Milk

|

Did you know that the first food most people ever have is milk? Made in the mammary glands of lactating mammals, milk is often called the "perfect" food. No other substance, on its own, is able to sustain life or support the rapid growth and development in young mammals as milk. That's because milk has been "formulated" over millions of years of evolution to contain all the nutrients in just the right balance to allow every cell in a young body to grow and flourish. But milk isn't just for babies, it contains vital nutrients and compounds that can help keep us healthy throughout our lives. When we're young, we all have a digestive enzyme called lactase that allows us to properly digest the sugar called lactose that's found human (and cow's) milk. Most mammals (including humans) are genetically "wired" to produce less and less lactase as they get older, making milk less palatable. This is done to encourage weaning. However, over the past 10,000 years humans have genetically evolved to keep expressing high levels of this enzyme, meaning that many adults can still enjoy milkshakes, ice cream, or even a nice cold glass of milk with a meal.

And it's great that we don't have to worry about hidden pathogens in our milk anymore, which used to be a major cause of foodborne illnesses. Louis Pasteur invented pasteurization in the mid-1800's, which is a process that heats milk up to a specific temperature (depending on what's being pasteurized) and then quickly cools it, maintaining the flavour, freshness, and nutrients. Contradictory to what raw-milk activists might say, pasteurization doesn't actually affect the nutritional quality of milk, instead, makes it safer for consumers [Macdonald]. In its fermented form, milk can be enjoyed as yogurt, sour cream, cheese, buttermilk, and many other delightful dairy products. Milk can also be processed to produce butter, sweetened condensed milk, or mixed with other products to create milk chocolate and, of course, chocolate milk. A favourite for kids, chocolate milk is not only delicious, but has been proven to be the ideal post-exercise drink because it appears to offer the perfect balance of healthy proteins, protective polyphenols and carbohydrates [Karp, Peschek, Pritchett]. Whether you prefer white or chocolate, milk of any colour is an amazing liquid filled to the brim with a myriad of minerals, healthy fats, proteins, and plenty of amazing micronutrients. Fresh, delicious, and udderly nutritious, milk is a great way to stay healthy throughout the day!

Milk Allergies

|

| Figure 2. A cow's milk allergy graphic |

| http://rlv.zcache.com/new_refined_version_available_stickers- rd5e1605806f64a318170ea7b02690c4f_v9waf_8byvr_512.jpg |

An allergy is an immune response to a harmless allergen that the body considers dangerous. Cow's milk allergy (CMA) affects 0.1% - 0.5% of adults, and typically develops during infancy, where it affects 2%-3% of one-year-olds [Crittenden/Skripak/Høst]. CMA is different from lactose intolerance, because lactose intolerance is not moderated by the immune system [Bahna]. In the case of CMA, certain bovine milk proteins will bind to immunoglobulin E causing a cascade of histamine release, and voila: an allergic reaction [Gould/Crittenden]. This type of allergic reaction can cause hives, a runny nose, swelling, coughing, wheezing and vomiting [Caffarelli]. A stronger immune response is indicative of a sustained allergy, and possibly other allergies [Høst/Skripak]. CMA can also be non-immunoglobulin E mediated, and this type of CMA is more common in adults. It is also characterized by a slower allergic reaction [Crittenden]. Symptoms associated with the adult form of CMA include eczema, inflammation of the colon, poor growth, and vomiting [Caffarelli]. Like many allergies, CMA can be beaten! Most children outgrow their allergy during their first year of life, and upwards of 80% are no longer allergic after infancy [Høst/Caffarelli].

Bottom Line: Milk allergy is rare, and children are likely to outgrow it!

Lactose Intolerance

|

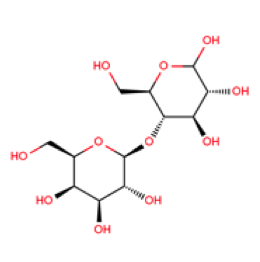

| Figure 3. Structural diagram of lactose |

While you have probably heard of lactose intolerance, it may surprise you to know that it happens over time, naturally. Lactose is a sugar present in many dairy products. In fact, it is the only sugar in milk [USDA]! Found in the small intestine, lactase is the enzyme produced by the body that metabolizes lactose into two smaller sugars: galactose and glucose [Skovbjerg/SMPDB/Campbell]. Over time, lactase becomes less abundant in the intestine, a condition known as lactase non-persistence (LNP) [Baadkar]. This is due to weaning: lactase expression decreases as children are weaned off of milk, causing an inability to digest lactose - or lactose intolerance [Swallow, Brüssow]. The frequency of lactose intolerance ranges from 5% in Northern European countries (England, Scotland, Ireland, Scandinavia, and Iceland) to 71% in Italy (Sicily) to more than 90% in some African and Asian countries. Overall some form of lactose intolerance affects 75% of the global population [Di Rienzo]! The other 25% are known as lactase persistent (LP), because lactase activity remains high throughout their lives, allowing them to digest lactose [Troelsen]. Individuals with lactose intolerance will experience digestive-tract related symptoms after consuming lactose, such as abdominal pain, distension and diarrhea [Mattar]. More lactose intake will also result in more severe symptoms [Mattar]. On the bright side, the LP allele is dominant over the LNP allele, meaning that over time, it's likely that more people will be lactose tolerant [Burger].

Bottom Line: Lactose intolerance is a natural syndrome; its prevalence varies around the world.

Vital Vitamins

|

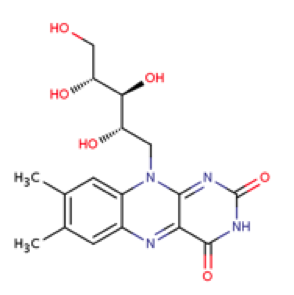

| Figure 4. Structural diagram of vitamin B2 |

Vitamins are essential nutrients that are used to help catalyze many important enzymatic processes throughout the body. Milk is a great source of four different vitamins: A, B2, B12 and D [USDA]. Vitamin A is an important nutrient for vision: it binds to a protein (rhodopsin) in the eye that absorbs light. Vitamin A is also important for maintaining immunity and enhancing skin health. Vitamin A deficiency, especially in young children, can lead to blindness [Higdon]. Vitamin B2 (also known as riboflavin) is needed for metabolism of fats, carbohydrates, and protein. Plus, vitamin B2 is necessary in many redox reactions of human metabolism, because it is part of the coenzymes FMN (flavin mononucleotide) and FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide), which are important because they move electrons from one reaction to another [Powers]. Vitamin B2 is also very important for maintaining healthy teeth, skin, hair, and nails, as well as thyroid function [Cimino]. Like its B-complex buddy, vitamin B12 (or cobalamin) is important for energy metabolism; it is also a cofactor for enzymes forming neurotransmitters and myelin sheaths (used to speed up neural transmission) in the nervous system [Higdon].

Vitamin D isn't really a vitamin in the strictest sense - it can be made through exposure to sunlight. But when there isn't sunlight, there is milk! Ingested vitamin D is inactive, as it has no metabolic effect. Thus, vitamin D has to become activated. This is done through the mitochondria of the liver and then the kidney, turning an inactive vitamin D into the hormonally active form of vitamin D: calcitriol [Deluca]! Vitamin D and regulates absorption of calcium and phosphate from the intestine. Vitamin D promotes the expression of calcium-absorbing proteins (TRPV6) in the gut, and works with parathyroid hormone to mobilize calcium from bone tissue (by promoting receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand) and to stimulate calcium reabsorption in the kidneys (using calbindin and TRPV5) [Deluca/Dussa/Van Cromphaut].

Bottom Line: Vitamins are essential for life, and milk has plenty of them. What's not to love about milk?

Minerals in Milk

Milk and calcium are synonymous. Everyone knows that milk is a great source of calcium, so maybe it's time the other minerals in milk got some attention. Milk is also rich in phosphorus and iodine: with a cup of 1% milk containing 23% of the daily value (DV) of phosphorus and 30% of the DV of iodine. [Susan Church/USDA]. Iodine is most important for the formation of thyroid hormones such as thyroxine. Thyroxine is produced when iodine atoms attach to the amino acid tyrosine, and is important in optimal thyroid function. Thyroid hormones control many metabolic-related processes in the body, including heart rate and body temperature. When you lack sufficient iodine, goitres can develop: which is a swollen thyroid gland that results from overproduction of tyrosine [Vanderpump].

|

| Figure 5. Image of a bone |

Phosphorus is used throughout the body, often in the form of phosphate salts or phosphate conjugates such as ATP and phospholipids. Phosphates are important in energy storage (ATP), nucleic acids (AMP, GMP, CMP, TMP) and membranes. Phosphorus and calcium (nearly 30% of the DV in a cup of 1% milk) form hydroxyapatite, which is found in bones and teeth [USDA/Uenishi/Johansonn]. This compound might be responsible for the pH buffering effect of milk that prevents damage to tooth enamel and roots [Johansson]. Furthermore, phosphorus and calcium contribute to the remineralization of tooth enamel - an important step in preventing cavities [Kashket]. The collective activity of minerals in milk have been shown to reduce blood pressure - a risk factor in cardiovascular disease [Ralston].

Many minerals in milk contribute to lowering blood pressure. Potassium, present in milk in small concentrations (10% of the DV in a cup of 1% milk), reduces blood pressure by stimulating the sodium-potassium pump (Na-K ATPase) [USDA/McGrane]. Calcium reduces blood pressure, albeit slightly, through a plethora of pathways (from parathyroid hormone to manipulation of the nervous system) [Jorde/Hatton]. Phosphorus also acts as a hypotensive agent, though its mechanism of action remains elusive [Elliott]. Magnesium, another mineral in milk (7% of the DV in a cup of 1% milk), raises levels of prostaglandin E (a vasodilator), induces endothelial-dependent vasodilation and blocks calcium channels, resulting in the production of powerful vasodilators nitric oxide and prostacyclin [USDA/Houston].

Besides blood pressure, minerals in milk appear to be effective against diabetes mellitus. Dairy consumption has been shown to reduce the risk of diabetes mellitus, and though the mechanism remains elusive, a few minerals in milk are likely contributors [Tong]. The release, activity, and disposal of insulin is dependent on magnesium [Swaminathan]. Studies show that reduced magnesium levels in the blood lead to insulin resistance, and increased magnesium consumption reduces diabetes risk [Dong]. Deficiency of calcium and vitamin D was shown to increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus [Pittas].

Bottom Line: Milk has a multitude of minerals, and they're all good for you!

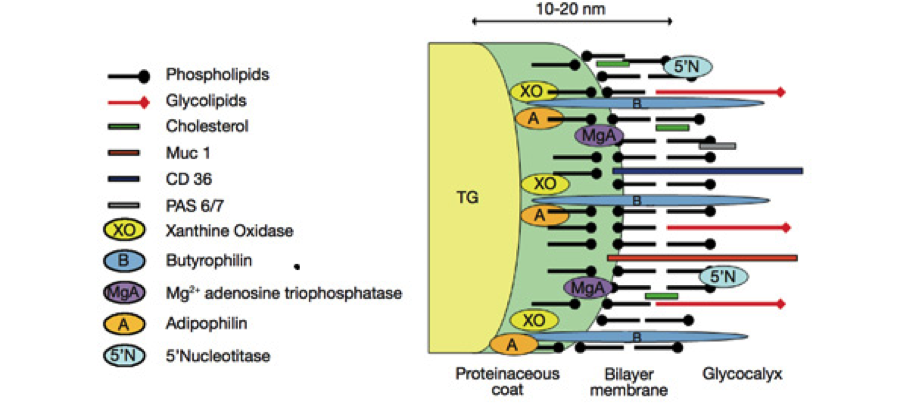

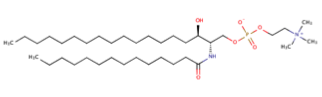

Magnificent MFGM

Milk is >88% water. The reason it is not a clear fluid is because it is actually a liquid suspension of tiny protein-fat globules. These tiny globules cause light to scatter which leads to the white colour of milk. The milk fat globule membrane (aka MFGM) is a phospholipid membrane surrounding the fat globules of milk. When milk is homogenized, the fat globules are broken up into smaller, more equal sizes, so that the milk fat doesn't separate from the rest and rise to the top. This process, though slightly affecting MFGM protein concentrations, does not considerably change the makeup of the membrane [Cano-Ruiz].

Turns out that the MFGM also has a lot of health benefits! In fact, in one study, the magnificent MFGM activated caspase-3, a well-known apoptosis inducer, causing apoptosis in colon cancer cells HT-29 [Zanabria]. But that's not all...

|

| Figure 6. Milk fat globule membrane structure. From Vanderghem C, Bodson P, Danthine S, Paquot M, Deroanne C, Blecker C. Milk fat globule membrane and bettermilks: from composition to valorization. BASE. 2010; 14(1): 485-500. |

Sensational Sphingomyelin

Phospholipids are an essential part of the milk fat globule membrane, and some of these phospholipids have been found to have some pretty beneficial health properties! One of these is sphingomyelin, which appears to have both anti-cholesterol and anticancer properties [Spitsberg 2005]! There is a lot of evidence to suggest that sphingomyelin regulates cholesterol levels, and vice versa [Ridgeway]. But how does this happen? Sphingomyelin's location in the cell membrane means that it's an important regulator, and this key fact means it has authority on what (and how much of) certain compounds can get in. For example, in human cells, it has been shown that sphingomyelin moves cholesterol from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it is important in the ER's homeostatic function [Ohvo-Rekilä, Ridsdale, Lusa]. But its relationship with cholesterol doesn't end there! The tail of sphingomyelin is very saturated, making it easier to stick to cholesterol. This natural attraction makes it simple for the two lipids to bind together and be excreted by the body together, which means the cholesterol isn't absorbed in the intestine [Eckhardt, Nilsson]! Sphingomyelin is able to stop cholesterol from being absorbed in the intestine through three methods: 1) it slows down the rate of cholesterol breakdown by the intestine, 2) it stops cholesterol from becoming more soluble (and therefore easier to integrate within the small intestine), and 3) it inhibits lipids from entering the intestinal cells [Noh].

|

| Figure 7. Structural diagram of sphingomyelin |

Also, sphingomyelin has been shown to prevent the development of cancer. Apoptosis of cancer cells can be induced through the activation of the cell signalling pathway by either tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) or stress activated protein kinase (SAPK), where the lipid molecule ceramide is synthesized, acting as a second messenger [Ballou, Obeid, Ohanian, Verheij]. Ceramide, and another metabolite called sphingosine act as cell growth suppressors, initiators, and differentiators [Hertervig]. In fact, ceramide was found to reduce proliferation of colon cancer cell HT-29 and induce apoptosis in prostate cancer cell line LNCaP, both through the previously-described mechanisms [Hertervig, Kimura].

Bottom line: Goodbye cancer and cholesterol! The sphingomyelin in the MFGM is yet another health benefit of milk.

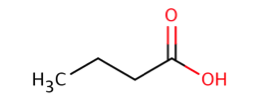

Saturated Fats

Any good chemist knows that oil and water do not mix. So, logically, in milk, the milk fats and the water should stay away from each other, right? But milk is a strange case. The many different fats and proteins found in milk form a unique structure known as a milk fat globule (MFG) [El-Loly]. Almost all of the fats in milk are triglycerides: a glycerol molecule attached to three fatty acids [Månsson HL]. Furthermore, most of the fatty acids in milk are saturated, meaning that each carbon is single bonded and the molecule is "saturated" with hydrogens [USDA].

|

| Figure 8. Structural diagram of butyric acid |

Though it is rich in triglyceride carriers, milk effectively contains many different fatty acids, some of which have very positive health effects. Milk contains some butyric acid (2% of all milk fat by weight): a short chain fatty acid that has long been known to have anticancer effects (especially for colon cancer) [USDA]. Butyric acid's anticancer effects arise from its role as an histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor [Davie]. As a result, high levels of butyrate favour an acetylated state of histones in the cell. Acetylated histones have a lower affinity for DNA than non acetylated histones, due to the neutralization of electrostatic charge interactions. By acting as an HDAC inhibitor, butyrate is able to inhibit the IFN-gamma/STAT1 signalling pathway [Zimmerman]. Butyrate inhibits activity of HDAC1 that is bound to the Fas gene promoter in T cells, resulting in hyperacetylation of the Fas promoter and up-regulation of Fas receptor on the T cell surface. As a result butyrate enhances apoptosis of T cells in the colonic tissue and thereby eliminates the main source of inflammation (IFN-gamma) and irritation in colonic tissues. Chronically irritated and inflamed tissues frequently become cancerous or ulcerated. Studies have also shown that butyric acid induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells, by affecting the expression of apoptotic regulating genes [Hague/Roy]. This was also the conclusion of research conducted on breast cancer cell lines [Mandal]. Other research has called butyrate a potent tumor stopping drug, that can induce differentiation and apoptosis in a "wide range" of tumor cell types [Parodi 1999/Parodi 1997]. Two other saturated fatty acids were found to have antimicrobial properties. Many studies shown lauric acid and capric acid are able to kill or inhibit various bacteria [Valipe/Nair]. In two separate studies, the fatty acids suppressed an inflammatory bacteria (Propionibacterium acnes), and also reduce inflammation through various genetic pathways (reducing IL-6 and IL-8 production, suppressing TNF-alpha secretion, inhibiting NF-kB activation and phosphorylating MAP kinases) [Nakatsuji, Huang]. Lauric and capric acid have also been shown to reduce inflammation by inhibiting COX-1 and COX-2, two enzymes responsible for prostaglandin formation (hormone-like lipid compounds that normally causes inflammation and pain) [Henry].

Regarding concerns about the consumption of saturated fats, it is important to eat in moderation. The link between saturated fat consumption and cardiovascular disease is hotly debated [Hu/Skeaff/Siri-Tarino/Chowdhurry/Walsh]. There is ample evidence to support that milk consumption does not negatively influence cardiovascular health [Soedamah-Muthu/Aslibekyan/Louie/Bel-Serrat/Rice]. Another study indicated consumption of dairy products proved beneficial to people with obesity, glucose intolerance, and hypertension. Furthermore, dairy consumption may be beneficial in warding off cardiovascular disease and has been shown to reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes [Soedamah-Muthu, Pereira, Choi, Liu, Forouhi]!

Bottom line: Some saturated fats can be crucial in warding off disease, and don't worry, they won't hurt you heart!

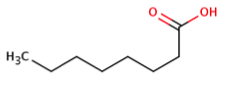

Milk's Medium-Chain Triglycerides

|

| Figure 9. Structural diagram of Caprylic acid |

Can fats really help you fight against getting fatter? Yes! Well, at least in the case of medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs). These saturated fats can be found in milk and are made up of 3 medium-length fatty acids attached to a glycerol [HMDB]. It's possible that consuming MCT's (as opposed to long chain triglycerides) can reduce fat accumulation, especially in people who are already overweight [St-Onge 2003, St-Onge 2008, Tsuji]. This is explained by the fact that medium-chain fatty acids are quickly oxidized in the liver, so a lot more energy is needed to metabolize them. The higher energy expenditure means that fat is "burned" as opposed to being deposited in the body [St-Onge 2002].

These likeable lipids have also been linked to cranking up the brain's metabolism, which has an effect on reducing the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease [Galvin]! When MCT's are oxidized by the liver, the process of ketogenesis occurs, producing ketone bodies [Sharma]. Ketone bodies are great at increasing metabolism because they increase levels of acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) and succinate, both of which are important parts of mitochondrial (and therefore metabolic) functions [Choi, Henderson]. When these bodies cross the blood-brain barrier, they can be an alternate fuel source for brain metabolism, replacing the typical glucose that is used. But how does this revved up metabolism link to Alzheimer's disease? You see, an early warning sign of the disease is decreased glucose metabolism in the brain, and so giving the brain a different fuel can help reduce the symptoms and prevent further onset of the disease [Sharma, Reiman].

Bottom line: When you drink milk, the fast mootabolism of the medium-chain triglycerides in your body helps in the fight against fat and Alzheimer's disease!

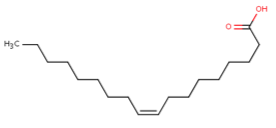

Unsaturated Fatty Acids

Milk is rich in a variety of fats, with unsaturated fatty acids being some of the most beneficial to health! Oleic acid is a promoter of heart health that makes up approximately 25% of milk fat [Haug]. Oleic acid isn't just in olive oil! An increased intake of foods rich in oleic acid has been linked to a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, as well as decreasing cholesterol concentrations [De Lorgeril, Kris-Etherton]. Also, when there is a high ratio between oleic acid (a monounsaturated fat) and polyunsaturated fats such as omega 3's and omega 6's, lipids do not accumulate on artery walls (called atherosclerosis). This is because oleic acid has been shown to inhibit gene expression of endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecules, meaning that plaques can't accumulate in the endothelial cells in arteries[Massaro/Nicolosi].

|

| Figure 10. Structural diagram of Oleic acid |

Another unsaturated fatty acid commonly found in milk is CLA, specifically known as cis-9, trans-11 isomer of conjugated linoleic acid (9c,11t-CLA or rumenic acid) [Månsson HL/Haug]. Various studies have shown that this fatty acid has amazing anti-cancer properties by reducing tumour growth, preventing proliferation of cancer cells, and inducing apoptosis of cancerous cells, especially in colon cancer [Park, Ochoa, Kelley]. To add on to this, CLA has anti-inflammatory properties! How does it do this? According to two studies, it suppresses COX-1 and COX-2, two enzymes that we said earlier are responsible for forming the pain and inflammation-causing prostaglandin, as well as suppressing another inflammation-causing factor called Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) [Iwakiri, Akahoshi].

Bottom line: Prevent atherosclerosis, cancer, and inflammation! Unsaturated fatty acids (oleic acid and conjugated linoleic acid) have amazing health properties that will help you live longer.

References

Introduction

- MacDonald LE, Brett J, Kelton D, Majowicz SE, Snedeker, Sargeant JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of pasteurization on milk vitamins, and evidence for raw milk consumption and other health-related outcomes. J Food Protect. 2011;74(11):1814-1832.

- Karp JR, Johnston JD, Tecklenburg S, Mickleborough TD, Fly AD, Stager JM. Chocolate milk as a post-exercise recovery aid.Int J Sport Nutr Exe. 2006;16(1), 78.

- Peschek K, Pritchett R, Bergman E, Pritchett K. The Effects of Acute Post Exercise Consumption of Two Cocoa-Based Beverages with Varying Flavanol Content on Indices of Muscle Recovery Following Downhill Treadmill Running. Nutrients. 2013;6(1): 50-62.

- Pritchett K, Bishop P, Pritchett R, Green M, Katica C. Acute effects of chocolate milk and a commercial recovery beverage on postexercise recovery indices and endurance cycling performance. Appl Physiol Nutr Met. 2009;34(6):1017-1022.

Cow's Milk Allergy

- Crittenden RG, Bennett LE. Cow's milk allergy: a complex disorder. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(6):582S-91S.

- Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, Wood RA. The natural history of IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1172-7.

- Høst A. Frequency of cow's milk allergy in childhood. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89(6):33-7.

- Bahna SL. Cow's milk allergy versus cow milk intolerance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89(6):56-60.

- Gould HJ, Sutton BJ, Beavil AJ, Beavil RL, McCloskey N, Coker HA, et al. The biology of IGE and the basis of allergic disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:579-628.

- Caffarelli C, Baldi F, Bendandi B, Calzone L, Marani M, Pasquinelli P. Cow's milk protein allergy in children: a practical guide. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:5.

Lactose Intolerance

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/154 (accessed 16 July 2014).

- Skovbjerg H, Sjöström H, Norén O. Purification and characterisation of amphiphilic lactase/phlorizin hydrolase from human small intestine. Eur J Biochem. 1981;114(3):653-61

- Wishart DS, Frolkis A, Knox C, et al., SMPDB: The Small Molecule Pathway Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D480-7.

- Campbell AK, Waud JP, Matthews SB. The molecular basis of lactose intolerance. Sci Prog. 2009;92(Pt 3-4):241-87

- Baadkar SV, Mukherjee MS, Lele SS. A study on genetic test of lactase persistence in relation to milk consumption in regional groups of India. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16(12):1413-8.

- Swallow DM. Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Annu Rev Genet. 2003;37:197-219

- Brüssow H. Nutrition, population growth and disease: a short history of lactose. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(8):2154-61

- Di Rienzo T, D'Angelo G, D'Aversa F, Campanale MC, Cesario V, Montalto M, et al. Lactose intolerance: from diagnosis to correct management. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17 Suppl 2:18-25.

- Troelsen JT. Adult-type hypolactasia and regulation of lactase expression. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;1723(1-3):19-32.

- Mattar R, Mazo DF. Lactose intolerance: changing paradigms due to molecular biology. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56(2):230-6.

- Burger J, Kirchner M, Bramanti B, Haak W, Thomas MG. Absence of the lactase-persistence-associated allele in early Neolithic Europeans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(10):3736-41.

Vitamins

- USDA - cited in lactose intolerance section

- Jane Higdon. Vitamin A. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/vitamins/vitaminA/ (accessed 17 July 2014).

- Powers HJ. Riboflavin (vitamin B-2) and health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(6):1352-1360.

- Cimino JA, Jhangiani S, Schwartz E, Cooperman JM. Riboflavin metabolism in the hypothyroid human adult. Exp Biol Med. 1987;184(2):151-153.

- Jane Higdon. Vitamin B12. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/vitamins/vitaminB12/ (accessed 6 August 2014).

- DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1689S-96S.

- Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E. Vitamin D. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289(1):F8-28.

- Van Cromphaut SJ, Dewerchin M, Hoenderop JG, Stockmans I, Van Herck E, Kato S, et al. Duodenal calcium absorption in vitamin D receptor-knockout mice: functional and molecular aspects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(23):13324-9.

Minerals in Milk

- USDA - cited in lactose intolerance section

- Susan Church. McCance and Widdowson's the Composition of Foods Sixth Summary Edition, 6th ed. United Kingdom: RSC Publishing; 2002.

- Vanderpump MP. The epidemiology of thyroid disease. Br Med Bull. 2011;99:39-51.

- Uenishi K. Phosphorus intake and bone health. Clin Calcium. 2009;19(12):1822-8.

- Johansson I. Milk and dairy products: possible effects on dental health. Scandinavian Journal of Nutrition 2002;46(3):119-122

- Kashket S, DePaola DP. Cheese consumption and the development and progression of dental caries. Nutr Rev. 2002;60(4):97-103

- Ralston RA, Lee JH, Truby H, Palermo CE, Walker KZ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of elevated blood pressure and consumption of dairy foods. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2012;26:3-13.

- McGrane MM, Essery E, Obbagy J, Lyon J, Macneil P, Spahn J, et al. Dairy Consumption, Blood Pressure, and Risk of Hypertension: An Evidence-Based Review of Recent Literature. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2011;5(4):287-298.

- Jorde R, Bonaa KH. Calcium from dairy products, vitamin D intake, and blood pressure: the Tromso Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(6):1530-5.

- Hatton DC, McCarron DA. Dietary calcium and blood pressure in experimental models of hypertension. A review. Hypertension. 1994;23(4):513-30.

- Elliott P, Kesteloot H, Appel LJ, Dyer AR, Ueshima H, Chan Q, et al. Dietary phosphorus and blood pressure: international study of macro- and micro-nutrients and blood pressure. Hypertension. 2008;51(3):669-75.

- Houston M. The role of magnesium in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13(11):843-7.

- Tong X, Dong JY, Wu ZW, Li W, Qin LQ. Dairy consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(9):1027-31.

- Swaminathan R. Magnesium metabolism and its disorders. Clin Biochem Rev. 2003;24(2):47-66.

- Dong JY, Xun P, He K, Qin LQ. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):2116-22.

- Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB, Dawson-Hughes B. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(6):2017-29.

Magnificent MFGM

- Choi HK, Liu S, Curhan G. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):283-289.

- Garrel DR, Verdy M, PetitClerc C, Martin C, Brule D, Hamet P. Milk-and soy-protein ingestion: acute effect on serum uric acid concentration. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(3):665-669.

- Cano-Ruiz ME, Richter RL. Effect of homogenization pressure on the milk fat globule membrane proteins. J Dairy Sci. 1997;80(11):2732-2739.

- Zanabria R, Tellez AM, Griffiths M, Corredig M. Milk fat globule membrane isolate induces apoptosis in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. Food Funct. 2013;4(2):222-230.

Phospholipids in the MFGM

- Spitsberg VL. Invited Review: Bovine Milk Fat Globule Membrane as a Potential Nutraceutical. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88(7):2289-2294.

- Kanno C. Secretory membranes of the lactating mammary gland. Protoplasma. 1990;159(2-3):184-208.

- Ridgway ND. Interactions between metabolism and intracellular distribution of cholesterol and sphingomyelin. BBA-Mol Cell Biol L. 2000;1484(2):129-141.

- Ridsdale A, Denis M, Gougeon PY, Ngsee JK, Presley JF, Zha X. Cholesterol is required for efficient endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport of secretory membrane proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(4):1593-1605.

- Lusa, S, Heino S, Ikonen E. Differential mobilization of newly synthesized cholesterol and biosynthetic sterol precursors from cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(22):19844-19851.

- Ohvo-Rekilä H, Ramstedt B, Leppimäki P, Peter Slotte J. Cholesterol interactions with phospholipids in membranes. Prog Lipid Res. 2002;41(1):66-97.

- Nyberg L, Duan RD, Nilsson Å. A mutual inhibitory effect on absorption of sphingomyelin and cholesterol. J Nutr Biochem. 2000;11(5):244-249.

- Eckhardt ER, Wang DQH, Donovan JM, Carey MC. Dietary sphingomyelin suppresses intestinal cholesterol absorption by decreasing thermodynamic activity of cholesterol monomers. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):948-956.

- Nilsson Å, Duan RD. Alkaline sphingomyelinases and ceramidases of the gastrointestinal tract. Chem Phys Lipids. 1999;102(1):97-105.

- Noh SK, Koo SI.Milk sphingomyelin is more effective than egg sphingomyelin in inhibiting intestinal absorption of cholesterol and fat in rats. J Nutr. 2004;134(10):2611-2616.

- Ballou LR, Laulederkind SJ, Rosloniec EF, Raghow R. Ceramide signalling and the immune response. BBA-Mol Cell Biol L. 1996;1301(3): 273-287.

- Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Ceramide: a stress signal and mediator of growth suppression and apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 1995;58(2):191-198.

- Ohanian J, Ohanian V. Sphingolipids in mammalian cell signalling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58(14):2053-2068.

- Verheij M, Bose R, Lin XH, Yao B, Jarvis WD, Grant S, et al. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380(6569):75-79.

- Hertervig E, Nilsson Å, Cheng Y, Duan RD. Purified intestinal alkaline sphingomyelinase inhibits proliferation without inducing apoptosis in HT-29 colon carcinoma cells. J Cancer Res Clin. 2003;129(10):577-582.

- Kimura K, Markowski M, Edsall LC, Spiegel S, Gelmann EP. Role of ceramide in mediating apoptosis of irradiated LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10(2): 240-248.

Saturated Fats

- El-Loly MM. Composition, Properties and Nutritional Aspects of Milk Fat Globule Membrane - a Review. Pol J Food Nutr Sci. 2011;61(1):7-32.

- Månsson HL. Fatty acids in bovine milk fat. Food Nutr Res.2008;52:10.3402/fnr.v52i0.1821.

- USDA - cited in lactose intolerance section

- Davie JR. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J Nutr. 2003;133(7 Suppl):2485S-2493S.

- Zimmerman MA, Singh N, Martin PM, Thangaraju M, Ganapathy V, Waller JL, et al. Butyrate suppresses colonic inflammation through HDAC1-dependent Fas upregulation and Fas-mediated apoptosis of T cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(12):G1405-15.

- Hague A, Elder DJ, Hicks DJ, Paraskeva C. Apoptosis in colorectal tumour cells: induction by the short chain fatty acids butyrate, propionate and acetate and by the bile salt deoxycholate. Int J Cancer. 1995;60(3):400-6

- Roy MJ, Dionne S, Marx G, Qureshi I, Sarma D, Levy E, et al. In vitro studies on the inhibition of colon cancer by butyrate and carnitine. Nutrition. 2009;25(11-12):1193-201

- Mandal M, Kumar R. Bcl-2 expression regulates sodium butyrate-induced apoptosis in human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7(3):311-8

- Parodi PW. Conjugated linoleic acid and other anticarcinogenic agents of bovine milk fat. J Daily Sci. 1999;82(6):1339-49.

- Parodi PW. Cows' milk fat components as potential anticarcinogenic agents. J Nutr. 1997;127(6):1055-60.

- Valipe SR, Nadeau JA, Annamali T, Venkitanarayanan K, Hoagland T. In vitro antimicrobial properties of caprylic acid, monocaprylin, and sodium caprylate against Dermatophilus congolensis. Am J Vet Res. 2011;72(3):331-5.

- Nair MK, Joy J, Vasudevan P, Hinckley L, Hoagland TA, Venkitanarayanan KS. Antibacterial effect of caprylic acid and monocaprylin on major bacterial mastitis pathogens. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88(10):3488-95.

- Nakatsuji T, Kao MC, Fang JY, Zouboulis CC, Zhang L, Gallo RL, et al. Antimicrobial property of lauric acid against Propionibacterium acnes: its therapeutic potential for inflammatory acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(10):2480-8.

- Huang WC, Tsai TH, Chuang LT, Li YY, Zouboulis CC, Tsai PJ. Anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory properties of capric acid against Propionibacterium acnes: a comparative study with lauric acid. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;73(3):232-40.

- Henry GE, Momin RA, Nair MG, Dewitt DL. Antioxidant and cyclooxygenase activities of fatty acids found in food. J Agr Food Chem. 2002;50(8):2231-2234. Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm E, Colditz GA, Rosner BA, et al. Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1491-9.

- Skeaff CM, Miller J. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: summary of evidence from prospective cohort and randomised controlled trials. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;55(1-3):173-201.

- Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease.Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(3):535-46.

- Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, Crowe F, Ward HA, Johnson L, et al. Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(6):398-406.

- Bryan Walsh. Ending the War on Fat, Time. 12 June 2014

- Soedamah-Muthu SS, Ding EL, Al-Delaimy WK, Hu FB, Engberink MF, Willett WC, et al. Milk and dairy consumption and incidence of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(1):158-71.

- Aslibekyan S, Campos H, Baylin A. Biomarkers of dairy intake and the risk of heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22(12):1039-45.

- Louie JC, Flood VM, Burlutsky G, Rangan AM, Gill TP, Mitchell P. Dairy consumption and the risk of 15-year cardiovascular disease mortality in a cohort of older Australians. Nutrients. 2013;5(2):441-54.

- Bel-Serrat S, Mouratidou T, Jiménez-Pavón D, Huybrechts I, Cuenca-García M, Mistura L, et al. Is dairy consumption associated with low cardiovascular disease risk in European adolescents? Results from the HELENA Study. Pediatr Obes. 2013; doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00187.x.

- Rice BH. Dairy and Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of Recent Observational Research. Curr Nutr Rep. 2014;3:130-138.

- Pereira MA, Jacobs DR Jr, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Kartashov AI, Ludwig DS. Dairy consumption, obesity, and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults: the CARDIA Study. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2081-9.

- Choi HK, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, Hu FB. Dairy consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):997-1003.

- Liu S, Choi HK, Ford E, Song Y, Klevak A, Buring JE, et al. A prospective study of dairy intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1579-84.

- Forouhi NG, Koulman A, Sharp SJ, Imamura F, Kröger J, Schulze MB, et al. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2014; doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70146-9

MCT's

- Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, et al., HMDB: a knowledgebase for the human metabolome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 37(Database issue):D603-610.

- St-Onge MP, Jones PJ. Physiological effects of medium-chain triglycerides: potential agents in the prevention of obesity. J Nutr. 2002;132(3):329-332.

- St‐Onge MP, Ross R, Parsons WD, Jones PJ. Medium‐Chain Triglycerides Increase Energy Expenditure and Decrease Adiposity in Overweight Men. Obes Res. 2003;11(3):395-402.

- St-Onge MP, Bosarge A. Weight-loss diet that includes consumption of medium-chain triacylglycerol oil leads to a greater rate of weight and fat mass loss than does olive oil. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(3):621-626.

- Tsuji H, Kasai M, Takeuchi H, Nakamura M, Okazaki M, Kondo K. Dietary medium-chain triacylglycerols suppress accumulation of body fat in a double-blind, controlled trial in healthy men and women. J Nutr. 2001;131(11):2853-2859.

- Galvin JE. Optimizing diagnosis and management in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2012;2(3):291-304.

- Sharma A, Bemis M, Desilets AR. Role of Medium Chain Triglycerides (Axona®) in the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;29(5):409-414

- Choi DK, Pennathur S, Perier C, Tieu K, Teismann P, Wu DC, et al. Ablation of the inflammatory enzyme myeloperoxidase mitigates features of Parkinson's disease in mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25(28):6594-6600.

- Henderson ST. Ketone bodies as a therapeutic for Alzheimer's disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(3):470-480.

- Reiman EM, Chen K, Alexander GE, Caselli RJ, Bandy D, Osborne, et al. Functional brain abnormalities in young adults at genetic risk for late-onset Alzheimer's dementia. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(1):284-289.

Unsaturated Fatty Acids

- Haug A, Hostmark AT, Harstad OM. Bovine milk in human nutrition-a review. Lipids Health Dis. 2007;6(1):25.

- De Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Salen P, Monjaud I, Mamelle N, Martin JL, et al. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1994;343(8911):1454-1459.

- Kris-Etherton PM, Pearson TA, Wan Y, Hargrove RL, Moriarty K, Fishell V, et al. High-monounsaturated fatty acid diets lower both plasma cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(6):1009-1015.

- Massaro M, Carluccio MA, De Caterina R. Direct vascular antiatherogenic effects of oleic acid: a clue to the cardioprotective effects of the Mediterranean diet. Cardiologia. 1999;44(6):507-513.

- Nicolosi RJ, Woolfrey B, Wilson TA, Scollin P, Handelman G, Fisher R. Decreased aortic early atherosclerosis and associated risk factors in hypercholesterolemic hamsters fed a high-or mid-oleic acid oil compared to a high-linoleic acid oil. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15(9):540-547.

- Månsson - cited in saturated fats section

- Park HS, Ryu JH, Ha YL, Park JH. Dietary conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) induces apoptosis of colonic mucosa in 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine-treated rats: a possible mechanism of the anticarcinogenic effect by CLA. Brit J Nutr. 2001;86(05):549-555.

- Ochoa JJ, Farquharson AJ, Grant I, Moffat LE, Heys SD, Wahle KW. Conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs) decrease prostate cancer cell proliferation: different molecular mechanisms for cis-9, trans-11 and trans-10, cis-12 isomers. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(7):1185-1191.

- Kelley NS, Hubbard NE, Erickson KL. Conjugated linoleic acid isomers and cancer. J Nutr. 2007;137(12):2599-2607.

- Iwakiri Y, Sampson DA, Allen KGD. Suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by conjugated linoleic acid in murine macrophages. Prostag Leukotr Ess. 2002;67(6):435-443

- Akahoshi A, Koba K, Ichinose F, Kaneko M, Shimoda A, Nonaka K, et al. Dietary protein modulates the effect of CLA on lipid metabolism in rats. Lipids, 2004;9(1):25-30.